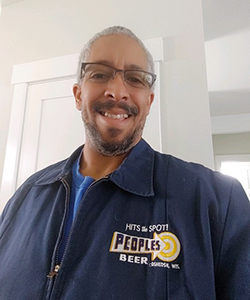

John Harry’s interest in beer antiques and memorabilia led him to choose beer history as the focus of his studies at UWM. (UWM Photo/Troye Fox)

If it takes beer to get people interested in history, that’s fine.

That’s the view of John Harry, a history graduate student who has focused his research on beer and Black capitalism.

In his early 30s, Harry decided he wanted to take his life in a different direction. He had an undergraduate degree in communications from UW-Stevens Point and had been working as a radio disc jockey when he took a trip to Germany with his sister. She was so impressed by his descriptions and knowledge of the sites they visited that she asked if he had ever thought about teaching history.

Craig Crosby is the son of Henry Crosby, one of the founders of Peoples Brewing Company. (Photo courtesy of Craig Crosby)

As he looked into university history programs and topics he could write about, his advisors suggested that his idea of focusing on “American history” was a bit broad.

“I had been collecting beer antiques and memorabilia for my whole life, so I said, ‘What about beer history?’ and they said that sounded fascinating.”

That subject started Harry off in a whole new direction. While researching an old brewery in Oshkosh, he came across another long-closed brewery that had been located across the street – “Peoples Brewing Company,” Wisconsin’s first and only Black-owned brewery.

“That was kind of my entry into beer history, but it’s not just beer history,” said Harry. “That’s what gets people interested, but it was more a story about Black capitalism…how the Black community was trying to build its own capitalism during the Civil Rights era.”

Black leaders bought brewery

As summarized in a story in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in November, Black community leaders and businessmen formed United Black Enterprises to invest in businesses that would support employment and growth in the Black community. They bought the brewery, which was originally founded in 1913, in 1970. Among the partners were Theodore Mack, a community activist and social worker who had worked as a production supervisor at Pabst, and Henry Crosby, a successful life insurance salesman.

Peoples Beer only lasted a few years under Black ownership, but Harry’s research led to unexpected connections and a broader exploration of Black entrepreneurship in Wisconsin.

When Harry gave a talk on the subject of Peoples at Vennture Brew on North Avenue, he met a guy wearing a Peoples Beer jacket. That was Craig Crosby, the son of Henry Crosby, one of the founders of Peoples. A retired lighting technician, Crosby was a beer memorabilia collector himself. Although Henry Crosby had died in 2012, Craig Crosby and his family were delighted that someone was taking an interest in the company’s history.

Crosby had a collection of Peoples memorabilia, and shared company and family history with Harry. “There were things that I knew that he didn’t, and so we were able to throw some stuff back and forth, and that was kind of cool,” Crosby said.

Broader goal than beer

Harry, a home brewer, even found the original recipe for Peoples and brewed up a batch for a project and shared a six-pack with Crosby.

“Through this we’ve become friends,” said Crosby. “I’ve told him his research made me feel really good. I’m glad that somebody took an interest in what my dad and the group tried to do. The fact that John was doing what he was doing to bring that information back out really made me happy. If my dad was still alive he’d approve.”

The goal of Peoples was broader than just brewing beer.

“Mack had made large investments trying to get the beer into the urban areas that he hoped would respond to the Peoples cause. He really wanted Peoples to be the beer of Black culture in America,” Harry wrote for the blog Good Beer Hunting. The brewery failed for a variety of reasons – the support from the Black community wasn’t as strong as the entrepreneurs had hoped, federal contracts that had been promised didn’t materialize and larger, white-owned breweries forced out many smaller brewers.

In addition to working with Crosby to gather more of the oral history of the company, Harry flew to Atlanta last January – just before the pandemic – to interview 84-year-old Pearl Mack, the widow of Theodore Mack. While the Mack family is working on its own testimonial and history, she took time to share some of her memories of Peoples.

Finding untold stories

Families can provide a unique perspective, Harry said. He hopes to continue sharing the story and working with the Black community on other research on Black business and entrepreneurship.

“One of the duties of historians in modern times is to find the stories that have not been reported on, and Black capitalism through the lens of brewing is one of those stories. In most academic work, it might be a footnote somewhere,” he said. “Being a white male who comes from privilege, I have to approach this with a sense that I have a lot of empathy, but this is not my experience. I have to tell the story from that perspective, being as respectful as possible.”

One factor that gets overlooked in a lot of discussion about racial equity is the challenge of access to capital, Harry said, and that’s a facet he wants to explore more. “Beer history is kind of an entry into a topic that otherwise might be more difficult for some people and communities to approach.”

Harry plans to receive his master’s degree in public history in May 2021 and go on for a doctorate, building on his research to look more broadly at Black capitalism in his dissertation. He’s also studying for a certificate in nonprofit management, and working at the Milwaukee County Historical Society.

‘Milwaukee’s a great city’

He came to UWM for the graduate degree because he liked the program, the people in the department and the city. “Milwaukee’s a great city with all the festivals and concerts in normal times. Even if these aren’t normal times, there’s no place else I’d rather be. I love being a Milwaukeean.”

And Harry has no regrets about his career switch. “The radio industry doesn’t pay that well, so the vow of poverty you have to take as a grad student wasn’t that much of a change,” he said with a laugh. “I always joke that I tried to find a career that paid less than radio and here I am.”

He has made his choice to make public history his future. “I’m not just stopping at a master’s. My wife is very supportive of all this. I’m a little older, so this is my chance to do this. Even though it’s hard sometimes, it’s very rewarding.”