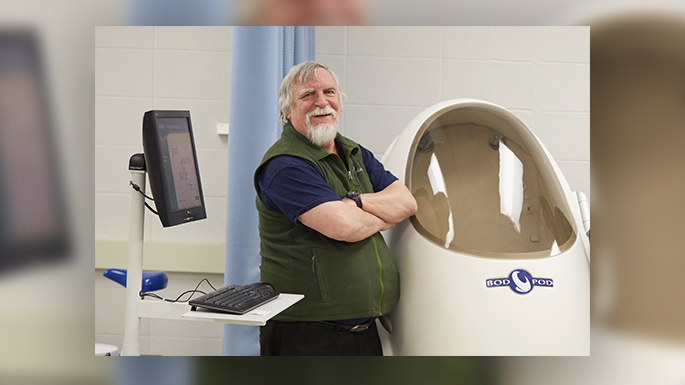

Carl Foster, an exercise and sport science professor at UW-La Crosse, has been named to the U.S. Speed Skating Hall of Fame. Foster is being inducted as a contributor to the sport after spending three decades as an exercise physiologist for Team USA.

Carl Foster and speed skating were an unlikely pair, but they couldn’t have been a more perfect match.

A Texas native who wasn’t exposed to the sport until after college, Foster was recently named to the U.S. Speed Skating Hall of Fame. He’s being recognized as a key contributor to the sport — the culmination of many years of work as an exercise physiologist for Team USA.

While his involvement with Olympic competition has dwindled in recent years, Foster has remained active as an exercise and sport science professor at UW-La Crosse, where he’s worked since 1998.

“It was a pleasant surprise, because there aren’t many non-skaters like me in that club,” Foster says. “I did a lot of work in speed skating 10 or 20 years ago, but not so much lately, so I didn’t know if I was seen as useful anymore. This is a nice pat on the back, and everyone likes a pat on the back.”

Foster earned his doctorate from the University of Texas at Austin in 1976, under the tutelage of exercise physiologist and celebrated running coach Jack Daniels.

Though he wasn’t a skilled runner himself, Foster shared Daniels’ keen interest in the mechanics of the human body, as well as his goal of helping top athletes avoid injury and improve their technique.

Foster soon began his career at Sinai Samaritan Medical Center in Milwaukee, where his boss, Michael Pollock, encouraged him to apply his knowledge to speed skating.

“I never skated on ice until I was 30-something, and I had no intrinsic feel for the sport,” he recalls. “I knew that, if I started asking questions, they’d inevitably be pretty dumb questions.”

Absorbing everything he could, Foster grew increasingly familiar with the ins and outs of speed skating. He spent a lot of time at the oval in Milwaukee, where many top speed skaters trained, talking with their coaches.

As it turned out, he was actually ahead of the curve — back then, the world of speed skating was relatively unexplored by scientists and researchers.

“There was almost no literature on the physiology of speed skating,” Foster says. “It was a really important sport in the Netherlands and Norway, and a minor sport everywhere else. In the United States, between the Olympics, it didn’t really exist in the mind of the public.”

Sharing his insight with Team USA, Foster left a small mark on the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, where American speed skaters won five gold medals and eight medals overall — both more than any other country.

In the years that followed, Foster became a fixture of U.S. Speed Skating, using cutting-edge science to help the country’s top skaters perfect their craft.

He went on to chair the Sports Medicine/Sports Science/Drug Testing committee for U.S. Speed Skating and received a research grant from the International Olympic Committee to conduct studies (along with fellow UWL professor John Porcari) at the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake.

By the time he scaled back his involvement with speed skating in the mid-2000s, Foster had built a reputation as one of the sport’s most influential scientific minds.

“He is one of those people who works tirelessly over a number of years with our athletes and coaches but is really in the trenches,” Bonnie Blair Cruikshank, a five-time Olympic gold medalist, told TeamUSA.org. “Those that worked with him know his dedication, long hours (and his commitment to) giving the athletes and coaches the best tools for success. He gave so much to our sport.”

While Foster is best known for his work with speed skaters, his two-plus decades at UWL may represent an even grander accomplishment.

As a professor and director of the Human Performance Laboratory at UWL, Foster has mentored hundreds of students who have gone on to successful careers in exercise and sport science.

He has written more than 300 scientific papers and contributed chapters to roughly 20 books.

And he has helped build, in his estimation, an outstanding exercise and sport science program. “I guess I’m biased, but I think we have the best program in the world,” Foster says. “If you look at how many papers we’ve published, how many people have been president of a major professional society, how many students are doing great work once they graduate, UWL is in a class by itself.”