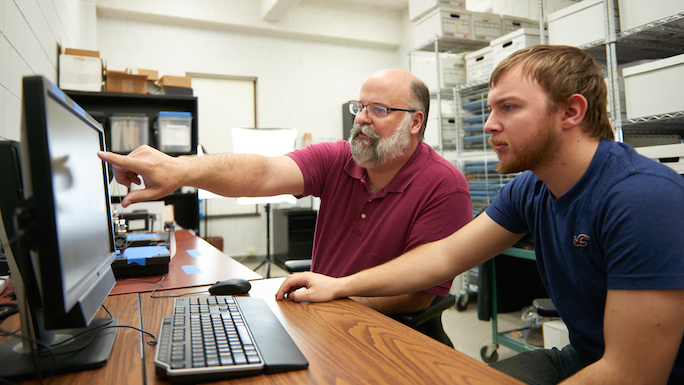

From left, David Anderson, UWL associate professor of archaeology, and UWL senior William Feltz are using cutting edge technology to make ancient artifacts easier to see — and feel.

Engravings of potentially the world’s earliest writing. A bust of one of the most famous women of the ancient world. Mummified bodies from northern Europe’s Iron Age. These artifacts preserved in museums across the world are not easily transported to a UW-La Crosse archaeology classroom. Yet David Anderson’s students pass them around to get a feel of what they are like.

Anderson, UWL associate professor of Archaeology and Anthropology, is bringing ancient archaeology into the 21st century — with only his digital camera, 3D printer and an inexpensive computer software program. Using a process called photogrammetry, he takes many photos of artifacts from multiple angles during his travels to museums and archaeological sites around the world. He then transforms them into moveable, 3D models on his computer screen, which can also be printed as teaching aids with 3D printers in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology. Anyone can view these 3D artifacts and other virtual models on Sketchfab, where people upload and share 3D content from around the world.

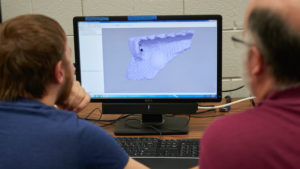

Feltz says for each pottery fragment he took about 90 photos while turning the object on a rotating tray. The most difficult part of the project was developing a system to creatively prop up the 500-700-year old artifact without damaging it.

Anderson says photogrammetry allows his students to experience archeological finds beyond a textbook description or 2D image, helping them gain a deeper understanding of the topic while also preparing them for a future in archaeology.

“It’s catching on so fast that if we are not teaching it, our students will be light years behind,” he says.

Anderson has been invited to travel to several U.S. museums and to Egypt this summer to instruct staff from various projects in the use of the technology.

Archaeology major William Feltz built his senior thesis project around photogrammetry. He added 3D representations of prehistoric pottery fragments from the Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center collection to the resources currently provided on the MVAC website, which include written descriptions and hand-drawn illustrations of artifacts.

Feltz’s work specifically focuses on 3D computer models that represent different phases in Oneota culture when ceramic pots were decorated differently along the rims. The viewer can move and manipulate a broken piece of pottery to examine small details that differentiate one fragment from another, which can be hard to distinguish in a 2D drawing.

“They can also be printed out for someone to hold and feel the object without needing to be in vicinity of MVAC, or for these objects to be outside the preservation box,” explains Feltz.

Relatively inexpensive computer software is used to transform the images of the artifact — a prehistoric fragment of pottery— into an 3D model on the computer screen, which can be moved and manipulated to see all sides and dimensions.

One of the goals of his thesis project is to show photogrammetry is a viable method for documenting and sharing artifacts at a time when it is not universally accepted as a worthwhile technique among archaeologists.

“Some don’t know how do it, and some don’t do it because they think it’s expensive — but all they need is a computer and a digital camera — most mobile phone cameras work fine,” explains Feltz. “The only expense is the computer program.”

Feltz was able to purchase an academic license for the computer software to convert the photo images into 3D models with an undergraduate research grant for about $500, so he could work on the project from home. Now that his project is complete, the 3D pottery fragments are live on the MVAC website. They are also available to anyone in the world on Sketchfab.

Feltz said he was “fascinated” to initially try photogrammetry in Anderson’s Research Methods in Archaeology (ARC445) class where students created their own 3D model of a grave stone.

“I loved the entire process,” says Feltz. “I liked the idea of using future technology to study ancient cultures … and there is still so much potential for photogrammetry that still has yet to be developed.”

Feltz holds a pottery fragment and a 3D printed model of one. After graduating, Feltz will begin work as a field technician for a Colorado State University archaeology excavation project at Ft. McCoy to analyze archaeological remains from the site prior to building.

The use of photogrammetry isn’t reserved for archeologists. It has applications across many disciplines, and is catching on at UWL. In the Biology Department, Anderson has shared tips and techniques with Assistant Professor Eric Snively, who specializes in vertebrate functional anatomy and paleontology. Anderson also consulted on how to use it in human anatomy courses.

Anderson first started trying photogrammetry four years ago, and started teaching it three years ago. He’s found it not only aids in teaching and student research experience, but it is also an impressive tool for work in the field. It speeds up the process of recording archaeological excavations from hours to minutes, he says. The ability to quickly document sites is of particular importance when uncovering human remains, which can begin to deteriorate when they are exposed to the sun and air, he explains.

Although photogrammetry can be done with a simple mobile phone camera, the results are much more detailed than hand-written notes, says Anderson. The process can be as accurate as being able to measure a hairline fracture along the surface of prehistoric pottery with 0.1 mm accuracy, notes Feltz. Using his 3D computer models Anderson has been able to look back at past digs, and re-evaluate the exact position of remains or even zoom in to look at at the smallest detail he may have missed during the initial excavation.

The technology has also expanded the ways archaeologists can help the public to engage with archaeology — even from a great distance, he says.

“The ability to virtually “handle” artifacts from museums and sites around the world as though they are right in front of them creates a new connection between our present and our past,” he says.

View a Sketchfab 3D Model

William Feltz uploaded this pottery fragment from Oneota culture on Sketchfab.