UWL students Miles Martinez, left, and Lauren Brewer document archaeological materials in the UWL Archaeology Lab during the spring 2021 semester.

A Native American pageant that brought thousands of tourists to Wisconsin’s Apostle Islands a century ago is, again, taking the stage – this time for UW-La Crosse students.

The students in last fall’s Historical Archaeology class took part in an ongoing collaborative investigation of the heritage and history of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, one of Wisconsin’s 11 Native American nations. Throughout the semester, the class covered culture and research questions related to the last 500 years of history in North America.

Through the help of their instructor Heather Walder, who teaches in the UWL Archaeology and Anthropology Department, the students engaged with a variety of artifacts and archival materials in a unique service-learning environment. The effort was supported by a UWL Center for Advanced Teaching and Learning (CATL) course-embedded research grant.

Through the help of their instructor Heather Walder, who teaches in the UWL Archaeology and Anthropology Department, the students engaged with a variety of artifacts and archival materials in a unique service-learning environment. The effort was supported by a UWL Center for Advanced Teaching and Learning (CATL) course-embedded research grant.

Walder has been collaborating with the Red Cliff community by co-directing the Gete Anishinaabeg Izhichigewin Community Archaeology Project. Through the project, she is partnering with Red Cliff Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Marvin Defoe and North Dakota State University Assistant Professor John Creese.

With support and approval from the Red Cliff Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, the students re-examined archaeological and archival evidence related to events during the Apostle Islands Indian Pageant, which took place in Red Cliff, Wisconsin, in the 1920s. The students investigated archaeological materials collected in 1979 by a Beloit College archaeological survey on the north shore of Red Cliff Bay.

The materials are curated by Red Cliff tribal members and are on a temporary loan for this project. Though never fully studied, they include a valuable record of recent historical events. The pageant generated tourism, bringing thousands of visitors to Red Cliff in 1924-25 and receiving widespread regional news coverage.

“It is an important part of the history of early tourism in northern Wisconsin,” notes Walder. “It’s a research topic that remains important to Red Cliff’s community members today.”

UWL student Faith Kalvig works on documenting archaeological materials as part of a historical archaeology class that has worked to preserve the heritage and history of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, one of Wisconsin’s 11 Native American nations

Students learned about the history and significance of the pageant through video presentations from Defoe and historian Katrina Phillips, an assistant professor at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota and a Red Cliff tribal member.

Then, students worked in groups to investigate topics of interest to Red Cliff members and themselves. They researched those topics and produced written reports about their assigned archaeological materials.

In their research, they identified artifacts, such as decal-decorated ceramic plates and cups, glass containers and “depression glass,” metal objects from domestic or structural use, construction materials, and other refuse commonly recovered from early 20th century activity areas.

In their reports, students included historical backgrounds, archival and genealogical research, photographs and descriptions of diagnostic archaeological artifacts, and discussions of their significance to the archaeological site at Red Cliff where they were recovered.

Walder says students contextualized the objects they examined within a broader historical framework, illustrating their significance to understanding the lives of past Red Cliff community members. At semester’s end, student groups shared their findings in video presentations to the Red Cliff Tribal Historic Preservation Officer and guests.

“As part of this work, the students gained firsthand experience collaborating with an Indigenous community on an archaeological project and learned the value and importance of collaborative research in historical archaeology,” notes Walder.

Elisabeth Primrose, a senior majoring in history with a minor in archaeological studies, says the most important takeaway from the class was the mindfulness of descendant communities in archaeological work.

“It is so easy for us to get wrapped up in the finding or treasure hunting aspect because making an amazing discovery is a really exciting part of archaeology,” Primrose explains. “But, I think there’s also a really beautiful side to archaeology when you can find something valued to the descendant community and really serve the descendant community in that way.”

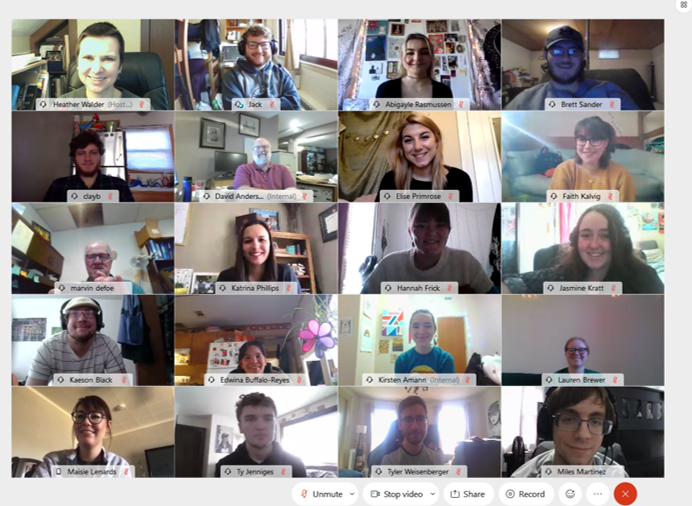

A screen capture of a UWL archaeology class during its final video presentation to the Red Cliff Tribal Historic Preservation Officer and guests in December 2020. The class that worked to preserve the tribe’s heritage and history.

Walder says the class left such an impression on some students that they have continued volunteering for the project in the lab and by transcribing handwritten 1979 field notes. Their work will assist in producing finalized artifact inventories. The students plan to create a video summary of their work to share on the Red Cliff Tribal Historic Preservation Office’s webpage.

Walder says the course-embedded research also provides background for a collaborative archaeological field season planned this summer.

“We hope that this project will continue to foster ongoing engagement, as undergraduate students work for and with the Red Cliff community to bring history to life,” she says.