UW-Stout environmental science students walk through a prairie at Menomin Park near Lake Menomin while doing plant research.

On a recent fall morning, leaves falling through a blue sky, small groups of University of Wisconsin-Stout students walked through shoulder-high grass on a prairie.

At Menomin Park, near Lake Menomin, they high-stepped over the dense growth wet with dew, then dropped plastic rings the size of Hula Hoops over spots they previously had marked with little red flags — using a smartphone app to pinpoint the spots.

Students Ben Ebben and Cristian Ayalo-Carpintero prepare to identify plants. The plastic ring was used to determine a consistent sample area.

The environmental science majors kneeled and used their hands to separate what was growing in the ring, plant by plant. A field guidebook helped confirm their hunches: cordgrass, big bluestem, bergamot, round-headed bush clover, common mullein, Kentucky bluegrass and more.

They took photos and notes and moved onto the next plot, sometimes crossing paths with another pod of students, all wearing face masks.

To reach the prairie, they had to drive to the edge of town near the 3M factory, then hike about a half-mile from the park’s trailhead down a hill and through a wooded area.

This was the type of applied learning they expected, and still are receiving despite COVID-19, when they chose UW-Stout.

“I am very happy to still be able to do hands-on work in the field during the pandemic, even if we need to wear masks and if the experiment will take a little longer because of distancing and limiting personal contact,” said Keaton Kuzel, of Lino Lakes, Minn., a senior.

“I feel like it is impossible to learn stuff like this by just watching videos of someone doing it and answering questions about what they did. I think our professors are doing an excellent job of helping us learn during the pandemic while practicing safety precautions at the same time,” he added.

A student uses his smartphone to help with plant identification.

Students made weekly trips to the park early in the semester. Their work is part of a project with Conservationist Dan Prestebak of Dunn County Land and Water Conservation and Manager Scott Nabbefeld of Dunn County Facilities and Parks to develop a vegetation management plan for the 34-acre prairie areas on the north end of the 147-acre park.

About a half-dozen student teams in the Restoration Ecology course each will develop a prairie management plan, based on their research, and present them to the county, with the hope their plan is chosen.

The project is a continuation of work last year by two students, who created habitat units as part of a capstone course in the major, said Assistant Professor Keith Gilland, who has a Ph.D. in plant ecology.

“Now we’re taking one of those management units to develop a plan that future iterations of my restoration class, and other environmental science classes, can work to implement,” Gilland said.

“I envision each time I teach restoration that we work on a management plan for a new section of the park while working on the restoration activities suggested in a previous semester’s class to get hands-on experience with those techniques, such as planting seeds or plants, removing invasive plants and applying herbicide,” he said.

Gilland, working with University Archives, found references to UW-Stout students doing research at the park going back to the early 1970s.

Learning in the field

Gilland wore a red flannel shirt over a T-shirt with a baseball-style cap. “It’s not a bad place to spend an October morning. Students love being out here. It’s why they came to UW-Stout,” he said.

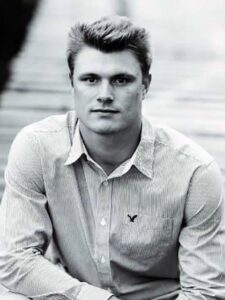

Keaton Kuzel

Kuzel concurred. “Classroom time is important, but I think doing work in the field helps me learn faster and helps me understand the concepts better. I value our time in the field because I know a lot of students at other universities and colleges don’t get opportunities for hands-on learning like this, and it is good experience for future internships and jobs,” he said.

Kuzel’s program concentration is in natural resources conservation, and he is minoring in geographic information systems.

He hopes to work in the conservation field when he graduates. Last summer, he interned in Minnesota helping with a carp management study on Prior Lake. “When you can learn stuff like that and have fun while you’re doing it, it just feels right,” he said.

Kuzel’s group included Peyton Maki, a junior from Rosemount, Minn.; Izzy Krieger, a sophomore from Fontana; Kyle Baemmert, a junior from Kiel; and Chris Jones, a senior from Racine.

Maki appreciated being outdoors, standing in the middle of wild things, and connecting firsthand to what they are learning in the classroom. “Most people avoid spots like this. Learning about plants gives you a greater appreciation for the ecosystem,” he said.

Jones noted that the park has about 15 user groups, including hikers, bird-watchers and mountain bikers, and that those users’ needs should be considered when developing a management plan.

Gilland’s class includes other outdoor field experiences, including the Chippewa River bottoms at Dunnville, a trout stream and the Hoffman Hills State Recreation Area oak savannah prairie restoration project. Students meet conservation professionals who are doing the kind of work students hope to do when they graduate.

- Menomin Park, near Lake Menomin, has 34 acres of prairie and 147 acres total.

- Student Sarah Stein leans down to photograph some plants at Menomin Park.

- Students photograph a plant.