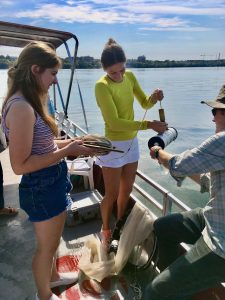

On a sunny afternoon in late September, a group of undergraduate students boarded Limnos II, UW-Madison’s Center for Limnology (CFL) pontoon boat, for a field trip on Lake Mendota with CFL director, Jake Vander Zanden. Onboard, they learned about the formation of Wisconsin’s lakes, tried their hand at using limnological tools like Secchi disks and zooplankton nets, and developed a better understanding of the many challenges facing our state’s abundant freshwater resources.

But these students weren’t part of the usual fall semester Zoology 316 class. They weren’t headed out for the annual field trip that’s part of the longest running limnology class in the world.

One of those classes is what led to the students being out on the lake with Vander Zanden. It was, he says, the first introduction to freshwater or “Freshwater 101” course being taught in the UW System as part of a state-wide initiative called the Freshwater Collaborative of Wisconsin (FCW). This small group was made up entirely of freshmen taking part in a brand new first-year interest group course called “Freshwater: Past, Present, and Future.” And, as part of the program, the 16 participants would spend their first semester on campus all taking the same set of three science-based courses organized around this freshwater theme.

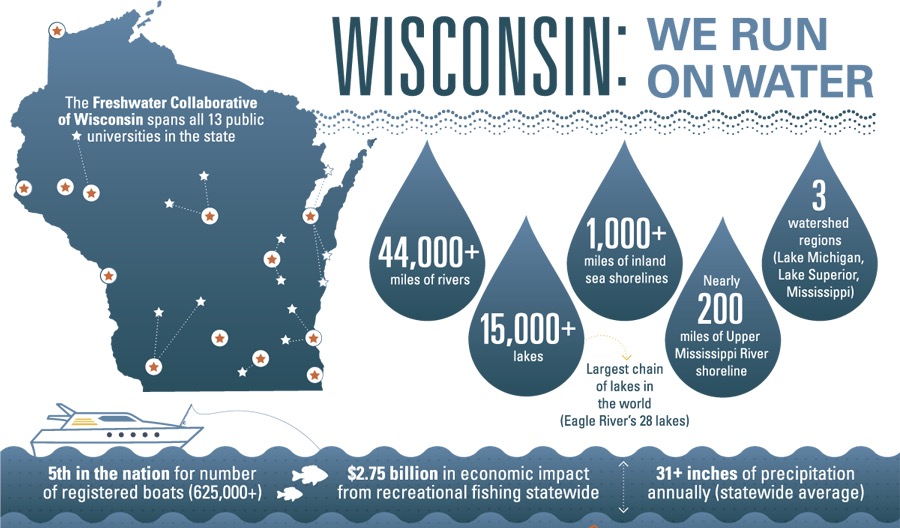

Bounded by two Great Lakes and the Mississippi River – with 15,000 or so inland lakes and 44,000 miles of rivers and streams in between – Wisconsin is an ideal place to study freshwater ecosystems.

However, freshwater education and research across the state has too often been an independent pursuit. While, for example, a scientist at UW-Milwaukee and UW-Superior might both be studying similar phenomena on large lakes, there’s just so much water research going on in the state, that they may not be aware of each other’s work. There simply hasn’t been a lot of coordinated collaboration.

The FCW was created to fix that problem and, according to the collaborative’s mission statement, “train the next generation of water researchers and problem solvers and to establish Wisconsin as a global leader in water-related science, technology and economic growth.”

“The initial support allowed us to begin creating truly hands-on field experiences for current and prospective UW students, providing them opportunities to go beyond their home campus and to learn about freshwater systems throughout our state,” Jablonski says. “We’ve also started developing new curriculum, such as the Freshwater 101 that launched in fall, which will be incorporated into programs at many of the campuses.”

The project was initially funded by just over $2 million from the UW-System and the Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation. And that early investment is already paying off, says FCW executive director, Marissa Jablonski.

Already, the FCW has fostered connections at campuses across the state and caught the eye of international scientists.

For example, faculty and students at UW-La Crosse are teaming up with colleagues across the state at UW-Whitewater for a research project exploring how pesticides impact fish. Another collaboration has the CFL’s Trout Lake Station partnering with a team down south at UW-Platteville to better understand our native freshwater mussel populations.

“Funding from the Collaborative has really been instrumental in kickstarting new partnerships among faculty at the UW campuses. Not only does that enhance the research that was already taking place, but it increases the diversity of experiences and mentorship available to students,” Jablonski says.

That project, co-led by Trout Lake Station director, Gretchen Gerrish, has also resulted in the development of an exchange program with Murdoch University in Perth, Australia. The collaboration will send Wisconsin undergrads Down Under and allow Murdoch students to train here in the “Freshwater Mussel Capital of the World.”

It’s exciting to see freshwater serving as a foundation for “strengthening connections among the 13 UW campuses,” says Vander Zanden. “The CFL already has long-standing relationships with faculty at many UW System campuses and one goal is to strengthen those ties.”

Another goal, he says, is to increase Wisconsin student’s access to learning opportunities across the state. “UW-Madison offers outstanding undergraduate research opportunities and the FCW will hopefully allow us to extend these to students from other UW System schools,” he says.

Beyond these new scientific ventures, the FCW is working to set young scientists on freshwater career paths, as well as explore the economic potential of clean, available freshwater for industry and tourism.

All in all, the project is a big win for the state of Wisconsin, its freshwater resources and the future scientists, policymakers and engineers who will make sure that our inland waterways remain an integral part of our lives.

By Adam Hinterthuer