As a toddler, Brooke Slavens loved playing make believe. Except for her, that involved taking temperatures, giving shots and role-playing other nurse duties with stuffed animals and her brother.

“I was just kind of drawn to help and care for others, including animals,” said Slavens, now a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Today, Slavens has carved out a unique career as an expert in human movement and rehabilitation. Her latest research on shoulder pain felt by manual wheelchair users could provide much-needed relief to children and adults alike.

The path to rehabilitation science

Slavens’ desire to help others led her to pursue a bachelor’s degree in biomedical engineering at the University of Iowa.

That pursuit placed her in a biomechanics lab working on spine specimens in animal cadavers. While the research itself was interesting, more importantly, it introduced Slavens to the power of working on a team in a lab environment.

“That’s what I really liked. We never worked by ourselves,” she said, underscoring how that collaboration across disciplines and departments informed how she conducts research today.

Teaming up with tech

As technology has evolved, in recent years, rehabilitation scientists and engineers have fueled an explosion of new solutions for people with limited mobility.

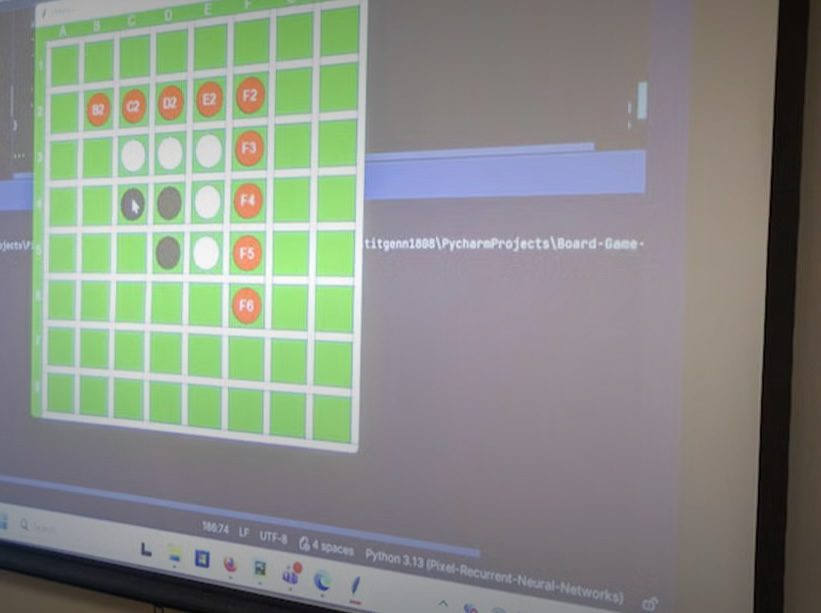

For example, Slavens and her colleagues are applying artificial intelligence (AI), imaging, motion capture technology and other high-tech devices to understand and support bodies facing limitations or injuries.

Sometimes that means providing a more tactile robotic prosthetic or wearable sensors to someone with a missing limb. In other cases, it involves using AI to compile symptoms and dynamic biometrics to better treat and support a disabled person.

“Being able to design custom, personalized medicine for individuals is the wave where things are going,” she said. “Even though a person might have a certain type of diagnosis, there’s a lot of different variations even by gender, by age, by our personal level of activity or personal interests and goals.”

Learning from child wheelchair users

Slavens’ latest research project is a shining example of that personalized care: Leading a five-year effort — with a team of interdisciplinary scientists — to better understand long-term shoulder pain and musculoskeletal conditions in people who have used wheelchairs since childhood. The project received more than $3 million in funding from the National Institutes of Health.

“We wanted to learn from the kids,” Slavens said.

Her unique approach invited more than 80 wheelchair users into UWM’s mobility lab to observe how they maneuver and rely on their shoulders in daily life. The team then evaluated the many types of shoulder movements that might affect a users’ well-being.

Part of the project’s inspiration was the fact that no treatment guidelines exist for children with spinal cord injuries. This means pediatric wheelchair users often receive the same care and recommendations as adults, despite having different and still-developing bodies.

“Kids are not just small adults,” Slavens said. “You can’t just take adult guidelines and paste them onto kids.”

Prioritizing preventative care

This work could help the 90% of wheelchair users who experience shoulder pain and related diseases throughout their lives. And it could prevent pain issues altogether in future populations.

The potential impact is significant, given that the average wheelchair user completes about 2,500 pushes a day, Slavens said. That is in addition to typical lifting, reaching and other daily upper-body tasks.

“We focus on preventing pain, keeping people happy and healthy, and helping them keep their independence,” she said. “Preventative medicine is exactly what a lot our field is trying to do right now.”

Written by Tree Meinch

Link to original story: https://uwm.edu/news/uwm-professor-uses-tech-to-tackle-wheelchair-shoulder-pain/